Imagine fire-safe communities where residents can live and evacuate in record time

Twenty-five years from today, Santa Ana winds will scream through Los Angeles on a dry autumn morning, turning a small hillside campfire into a deadly, fast-moving blaze.

At that moment, the city will spring into action.

Satellites will team up with anemometers, pairing live aerial footage with wind patterns to tell firefighters exactly where the fire is going. Fleets of autonomous Black Hawk helicopters and unmanned air tankers will fill the skies, dropping fire retardant in the path of the flames.

People in threatened neighborhoods will quickly run through to-do lists: close vents, check on neighbors, etc. Some renters and homeowners will arm fire-retardant sprayers on their roofs and jam valuables into fireproof ADUs tucked in their backyards. Others will have outfitted their super-smart homes with technology that cuts down on decision-making for an even quicker getaway. Apartment safety teams will follow their well-rehearsed plans to ensure evacuation.

Then, everyone will follow their community evacuation plan by driving their electric vehicles or ride-sharing to safety, eased along by a steady flow of green lights programmed by the city to divert all traffic away from the fire. Fleets of self-driving vans will circle back through the neighborhoods, picking up any stranded residents.

The scenario might seem improbable, but according to firefighters, architects and futurists, it’s a realistic outline of what L.A.’s fire defense could look like in 2050.

Devastating fires have pummeled Southern California in the last several decades, shifting the public conversation from fire suppression to fire preparedness and mitigation as governments begrudgingly acknowledge the disasters as regular occurrences. In the wake of the deadly January fires that burned through Altadena and Pacific Palisades, many people are wondering: Can we truly fortify our city against a firestorm?

Michael thinks we can. A Palisades resident whose clients include celebrities, he built his home to be fire-resistant knowing that, at some point, it would be subject to a firestorm.

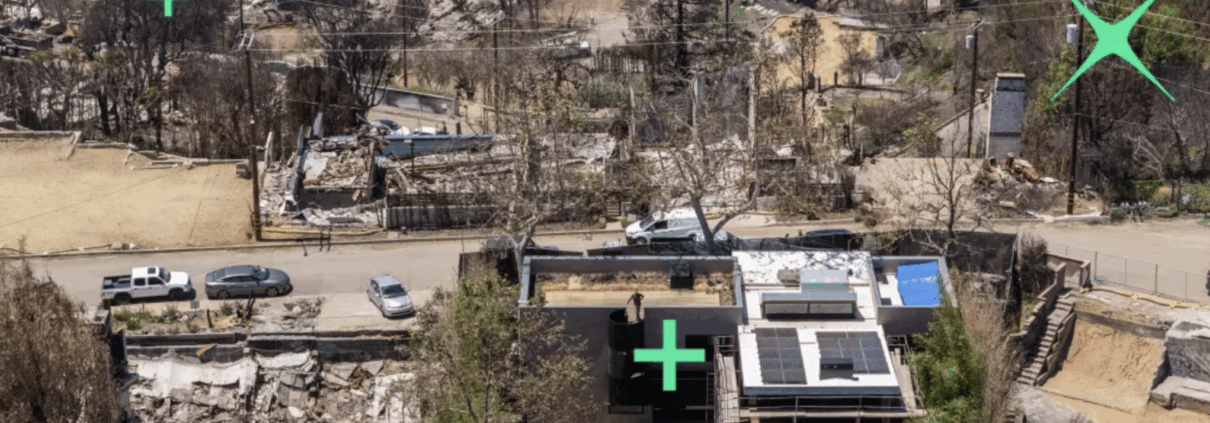

On Jan. 7, his entire street burned, but his house survived. Now, it serves as a blueprint for fire resistance.

“We built it to be able to withstand a small fire,” he said. “We never imagined our whole community would be erased.”

Michael’s home is wrapped in fire-resistant fiber cement-panel siding. The green “living” roof is topped with grass and more than 4 inches of fire-resistant soil. The windows feature three panels of quarter-inch glass, which lessen the possibility of breakage in the face of scorching temperatures and protect the interior from radiant heat — one of the primary ways fires can enter a home.

Before fleeing the fire, he loaded all his valuables into a room wrapped in concrete and equipped with a fire door capable of keeping out smoke and flames for three hours. He monitored the blaze from afar using security cameras. As the flames approached, he activated three sprinklers that sprayed fire retardant along the perimeter of the property, keeping the fire at bay.

Fire-proofing safeguards generally aren’t cheap. Fire-proof doors run from a few hundred dollars into the thousands, and fire-retardant sprinklers can cost tens of thousands of dollars, depending on the system. But Michael also installed some DIY upgrades for next to nothing, including dollar-store mesh screens on all his vents to block embers from entering — another frequent cause of fires spreading.

Every improvement helps, but the harsh reality of the next 25 years is that across L.A., older structures that don’t comply with modern fire codes will burn. The collective hope is that by 2050, they’ll be replaced by fire-resistant homes, adding a herd-immunity defense to neighborhoods.

“The 1950s housing stock in the Palisades — smaller, older homes more vulnerable to fires — are all gone. I’m sad because I enjoyed the texture they brought, but whenever one burned, it made it likelier that the home next to it would also burn,” he said. “Now there’s a clean slate, so the neighborhood we build next will be more fire-resilient.”

“The housing replacement cycle is slow. It upgrades every 50 years or so, with 2% of homes being replaced per year,” said the chief executive of a resilient building company. “But large-scale incidents like fires or earthquakes are an opportunity for a migration to a better system.”

The company creates insulated concrete panels that are made with fire-retardant foam sandwiched between two wire-mesh faces, which are, in turn, wrapped in concrete.

The future of fire mitigation, he said, boils down to building with non-combustible materials.

“In California, 98% of homes have wood frames. All those homeowners have a future tragedy on their hands,” he added. “You can’t knock down all of California and start new, but you can mitigate portfolio damages by making new parts of the portfolio better.”

By 2050, he said, Californians should have a fire-proof place to store their assets in case of a fire — so they at least have something to get back to.

Some home builders and designers are offering fire-resilient designs as demand continues to grow in the wake of the fires. One major home builder recently unveiled a 64-home fire-resilient community in Escondido equipped with covered gutters, non-combustible siding and defensible space. A Santa Monica-based architectural firm offers fire-rated glazes and foam-retardant sprayers on its custom-built designs. By 2050, experts say, the vast majority of home builders will offer fire-resistant homes.

There’s a reason so many California homes are built with wood: It’s relatively cheap. There are plenty of futuristic building materials — including graphene, hempcrete and self-healing concrete — but they’re not cost-efficient for most home buyers. Even traditional concrete, which stands up to the elements better than wood, runs roughly 20%-50% more than wood for home building, and building a fire-resistant home adds tens of thousands of dollars to the building cost.

For one architect and futurist, the solution is a return to wood — mass timber, specifically.

In addition to teaching architecture at the University of San Diego, he is the founder of a home-building startup that says it can assemble a house in three days. To prove it, he put together a small prototype in his La Jolla backyard over a weekend in February. The 540-square-foot ADU is wrapped in 60 mass timber panels made of three 1.5-inch layers of plywood sealed together.

With traditional wood construction, the wood, studs and insulation leave plenty of room for oxygen, which fuels fires. With mass timber, the layers are sealed with no air gaps, making them much more fire-resistant. When exposed to fire, the mass timber charcoals and burns a half-inch every hour — so a 4.5-inch panel would last six or seven hours before fully burning.

“It’s like in forest fires where big, old-growth trees survive by charcoaling. The exterior chars, but the inside survives.”

Mass timber is a new trend in fire-proofing; in this year alone, there are multiple conferences across the country dedicated to the engineered wood.

A Portland-based architecture firm has helped pioneer the use of mass timber in the U.S., with projects ranging from corporate buildings to conservation centers. Mass timber projects are starting to sprout up across the Southland, including multi-family developments and office-retail complexes.

Though the backyard prototype is the only model so far, the startup has been flooded with inquiries after the January fires. The founder has told customers he can put a unit up in six weeks from start to finish, with 540-square-foot units running $300,000 all-in.

For him, the future is also about using new technology, such as robotic arms that assemble panels, to get more out of the materials we already use.

“By 2050, we’ll be mixing ancestral materials with high-tech solutions,” he said. “Think Star Wars: a lightsaber in a cave.”

In the meantime, he suggests that instead of tearing down the 1950s tinderbox houses strewn across L.A.’s fire-prone hills, we should tack mass timber panels onto their exterior or interior to give firefighters hours, instead of minutes, to try to save homes once they catch on fire.

Mass timber is one of multiple approaches that would make the job of the Orange County fire chief easier. He has been fighting wildfires for 47 years, but over the last few decades, as blazes penetrate deeper into cities, he’s dealing with a different kind of problem: urban conflagrations.

Wildfires burn forests or brush, but urban conflagrations are fires that burn through cities. They’re becoming more common, and the toxic fumes released when homes burn present new dangers to his squad.

“These are typically wind-driven fires, and they’re driving smoke into the lungs of firefighters,” he said. “We do blood draws, and early testing shows higher levels of heavy metal.”

Firefighters have a 14% higher chance of dying from cancer than the general population, according to a 2024 study, and the disease was responsible for 66% of career firefighter line-of-duty deaths from 2002 to 2019.

He hopes 2050 brings more safety precautions for his team, such as personal respirators for every firefighter and fleets of trucks that share their location in real time for better communication between departments. He imagines fleets of drones flying alongside firefighting aircraft.

He’s also optimistic about funding, saying he’s never seen so much legislative interest in putting money toward fire services as in the wake of the January fires. The Los Angeles Fire Department is one of the few city departments poised to gain new hires under a $14-billion spending plan released in April, which proposed adding 227 fire department jobs while cutting 2,700 jobs in other departments.

A few weeks after the January fires, a California Assembly bill was introduced to explore the use of autonomous helicopters to fight fires. The choppers, including Black Hawks traditionally used for military operations, can be remotely programmed to take off, find fires and drop water where it’s needed. By 2050, experts hope firefighting stations will have entire fleets at their disposal to limit risk to pilots during shaky weather conditions.

In March, a space tech company launched a low-orbit satellite designed to detect wildfires early. By 2030, they expect to have a fleet of 50 satellites circling the globe.

“The next few years are a pivotal moment for both fire services and citizens,” the fire chief said. “We have to get it right.”